INTRODUCTION

1 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

Section I. Anatomy of the

Digestive System

Section II. Functions and

Stages of the Digestive Process

Exercises

2 PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

Exercises

3 DISEASES AND DISORDERS OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL

SYSTEM

Section I. Diseases/Disorders

of the Upper Gastrointestinal System

Section II. Hernias

Section III.

Diseases/Disorders of the Lower Gastrointestinal System

Section IV. Diseases/Disorders

of the Accessory Organs

Exercises

4 INGESTED POISONS

Exercises

5 NASOGASTRIC INTUBATION

Section I. Preliminary Steps

Section II. Procedure for

Inserting the Nasogastric Tube

Section III. Procedure for

Removing the Nasogastric Tube

Exercises

6 ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

Exercises

7 HEPATITIS

Exercises

------------------------------

LESSON 1

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

Section I. ANATOMY OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

1-1. INTRODUCTION

a. Food is Essential to Life. Food is necessary

for the chemical reactions that take place in every body cell; for

example, formation of new enzymes, cell structures, bone, and all

other parts of the body that give the energy to supply the body's

needs.

Most of the foods we eat are just too large to pass

through the plasma membranes of the cells. The process of breaking

down food molecules for the body's cells to use is called digestion,

and the organs which work together to perform this function are termed

the digestive system.

b. Regulation of Food Intake. How much food we

eat is regulated by two sensations--hunger and appetite. When we crave

food in general, we are experiencing hunger, and when we want a

specific food, the correct term is appetite. The stronger of the two

sensations is hunger which is accompanied by a stronger feeling of

discomfort.

The hypothalamus is the control center for food

intake. There are a cluster of nerve cells in the lateral hypothalamus

(the appetite center) which send impulses causing a person to want to

eat. Another cluster of nerve cells tell the person he has had enough.

These cells are located in the medial hypothalamus and

called the satiety center. A person's food intake must be regulated to

prevent the digestive tract from becoming too full. The upper

digestive tract expands to let food enter the tract. Receptors in the

walls of the digestive tract are stimulated and send signals to the

satiety center, signals that tell the person he is full. He stops

taking in food, and the contents of the digestive tract are digested.

c. Digestive Processes. Five basic activities

help the digestive system prepare for use by the cells. These

activities are ingestion, peristalsis, digestion, absorption, and

defecation.

(1) Ingestion. Taking into the body of food, drink, or

medicines by mouth.

(2) Peristalsis. Alternating contraction and

relaxation of the walls of a tubular structure by which food is move

along the digestive tract.

(3) Digestion. The processes by which food is broken

down chemically and mechanically for the body's use. In chemical

digestion, catabolic reactions break down protein, lipid, and large

carbohydrate molecules we have eaten into smaller molecules which can

be used by the body's cells. Mechanical digestion refers to the

various movements which aid chemical digestion. Examples of such

movements are the chewing of food by teeth and the churning of food by

the smooth muscles of the stomach and the small intestine.

(4) Absorption. The taking up of digested food from the digestive

tract into the cardiovascular and lymphatic systems for distribution

to the body's cells.

(5) Defecation. The discharge of indigestible

substances from the body.

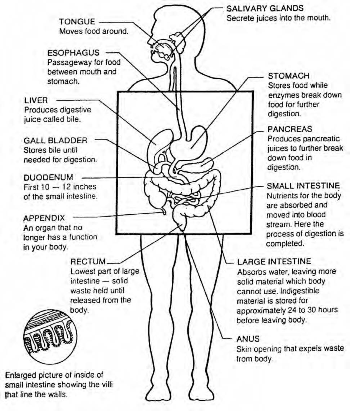

d. Organization of Digestive Organs. The

digestive organs are commonly divided into two main groups: the

gastrointestinal (GI) tract (also called the alimentary canal) and the

accessory structures.

(1) The gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The

gastrointestinal tract is a continuous tube which extends from the

mouth to the anus and which runs through the ventral body cavity. The

tube is about 30 feet long in a cadaver and a little shorter in a

living person because the tube's wall muscles are toned. From the time

food is eaten until it is digested and eliminated, it is in the

gastrointestinal tract. Muscular contractions in the walls of the GI

tract churn the food breaking it into usable molecules. The organs

which make up the gastrointestinal tract are the mouth, pharynx,

esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. These organs

are sometimes referred to as the primary organs of the digestive

system.

(2) Accessory structures. These structures include the

teeth, tongue, salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

Except for the teeth and the tongue, all the structures lie outside

the continuous tube which is the gastrointestinal tract. Secretions

that aid in the chemical breakdown of food are produced and stored by

these structures. Eventually, such secretions are released into the GI

tract through ducts in the body.

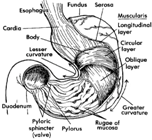

(3) General histology (structure of tissues). The

gastrointestinal wall has the same basic tissue arrangement from the

mouth to the anus. There are four coats (also called tunics): the

mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa (adventitia). The mucosa,

the inner tissue layer, contains blood and lymph vessels which carry

nutrients to other tissues and also protects the rest of the body

against disease. The submucosa is made up of loose connective tissue

and binds the mucosa to the next layer which is the muscularis.

Skeletal muscle in the muscularis of the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus

produce voluntary swallowing. The outer layer of tissue is the serosa.

NOTE: Remember that the GI tract carries food which often

contains bacteria.

From The

Gastrointestinal System