Operational Obstetrics & Gynecology

Abnormal Pregnancy

Miscarriage (Spontaneous Abortion)

Miscarriage is the layman's term for spontaneous abortion, an unexpected 1st trimester pregnancy loss.

Since the term "spontaneous abortion" may be misunderstood by laymen, the word "miscarriage" is sometimes substituted.

Loss of a pregnancy during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, at a time that the fetus cannot survive. Such a loss may be involuntary (a "spontaneous" abortion), or it may be voluntary ("induced" or "elective" abortion).

Abortions are further categorized according to their degree of completion. These categories include:

-

Threatened

-

Inevitable

-

Incomplete

-

Complete

-

Septic

Such losses are common, occurring in about one out of every 6 pregnancies.

For the most part, these losses are unpredictable and unpreventable. About 2/3 are caused by chromosome abnormalities incompatible with life. About 30% are caused by placental malformations and are similarly not treatable. The remaining miscarriages are caused by miscellaneous factors but are not usually associated with:

-

Minor trauma

-

Intercourse

-

Medication

-

Too much activity

Following a miscarriage, the chance of having another miscarriage with the next pregnancy is about 1 in 6. Following two miscarriages in a row, the odds of having a miscarriage with the next pregnancy is still about 1 in 6. After three consecutive miscarriages, the risk of having a fourth is greater than 1 in 6, but not very much greater.

A threatened abortion means the woman has experienced symptoms of bleeding or cramping.

At least one-third of all pregnant women will experience these symptoms. Half will go on to abort spontaneously. The other half will see the bleeding and cramping disappear and the remainder of the pregnancy will be normal. These women who go on to deliver their babies at full term can be reassured that the bleeding in the first trimester will have no effect on the baby and that you expect a full-term, normal, healthy baby.

Treatment of threatened abortion should be individualized. Many obstetricians recommend bedrest in some form for women with a threatened abortion. There is no scientific evidence that such treatment changes the outcome of the pregnancy in any way, although some women may feel better if they are at rest. Other obstetricians feel that being up and active is psychologically better for the patient and will not change the risk of later miscarriage. Among these active women, strenuous physical activity is usually restricted, as is intercourse.

In an operational setting, bedrest may prove very useful. While you are not changing the outcome of the pregnancy (abnormal chromosomes will remain abnormal despite increased maternal rest), you may effectively postpone the miscarriage until a safer time. (days to possibly a week or two)

|

9-Week |

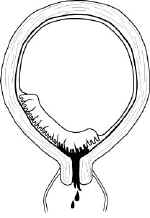

A complete abortion means that all tissue has been passed through the cervix.

This is the expected outcome for a pregnancy which was not viable from the outset. Often, a fetus never forms (blighted ovum). The bleeding and cramping steadily increases, leading up to an hour or two of fairly intense cramps. Then the pregnancy tissue is passed into the vagina.

An examination demonstrates the active bleeding has slowed or stopped, there is no tissue visible in the cervix, and the passed tissue appears complete. Save in formalin any tissue which the patient has passed.

RH negative women receive an injection of Rhogam (hyperimmune Rh globulin) within 3 days of the abortion. It may still be effective in preventing Rh sensitization if given within 7-10 days.

They are encouraged to have a restful day or two and a follow-up examination in a week or two. Bleeding similar to a menstrual flow will continue for a few days following the miscarriage and then gradually stop completely. A few women will continue to spot until the next menstrual flow (2-6 weeks later).

Women seeking another pregnancy as soon as possible are often advised to wait a month or two to allow them to re-establish a normal uterine lining and to replenish their reserves. Prolonged waiting before trying again is not necessary.

Some physicians recommend routinely giving a uterotonic drug (such a Methergine 0.2 mg PO TID x 2 days) to minimize bleeding and encourage expelling of any remaining fragments of tissue.

It also may increase cramping and elevate blood pressure.

Antibiotics (Doxycycline, amoxicillin) are likewise prescribed by some. While the usefulness of these medications in a civilian setting depends on circumstances, they are probably very wise in an operational setting, particularly where sanitation may be suboptimal.

If fever is present, IV broad-spectrum antibiotics are wise, to cover the possibility that the complication of sepsis has developed. If the fever is high and the uterus tender, septic abortion is probably present and you should make preparations for D&C (or Medical Evacuation if D&C is not available locally.

If hemorrhage is present, bedrest, IV fluids, oxygen, and blood transfusion may be necessary. Continuing hemorrhage suggests an "incomplete abortion" rather than a "complete abortion" and your treatment should be reconsidered.

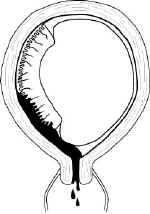

With an incomplete abortion, some tissue remains behind

inside the uterus.

With an incomplete abortion, some tissue remains behind

inside the uterus.

These typically present with continuing bleeding, sometimes very heavy, and sporadic passing of small pieces of pregnancy tissue.

When available, ultrasound may reveal the presence of identifiable tissue within the uterus. Serial quantitative HCG levels can be measured if there is doubt about the completeness of a miscarriage.

Left alone, some of these cases of incomplete abortion will eventually resolve spontaneously, but so long as there are non-viable pieces of tissue inside the uterus, the risks of bleeding and infection continue.

Treatment consists of converting an incomplete abortion into a complete abortion. Usually, this is done with a D&C (dilatation and curettage). This minor operation can be performed under local anesthesia and takes just a few minutes.

If D&C is not available, bedrest and oxytocin, 20 units (1 amp) in 1 Liter of any crystalloid IV fluid at 125 cc/hour may help the uterus contract and expel the remainder of the pregnancy tissue, converting the incomplete abortion to a complete abortion.

Alternatively, ergonovine 0.2 mg P.O. or IM three times daily for a few days may be effective.

If fever is present, broad-spectrum antibiotics are wise, particularly if D&C is not imminent.

Any tissue fragments visibly protruding from the cervical os can be grasped with a ring or dressing forceps and gently pulled straight out. This simple and safe procedure will have a beneficial effect on the bleeding.

Do not attempt to insert any instruments into the uterus unless you have had training to do this since you may cause more harm than simply leaving things alone.

If hemorrhage is present, bedrest, IV fluids, oxygen, and blood transfusion may be necessary.

The decision for medical evacuation is difficult. Moving the patient will usually increase the rate of bleeding. At the same time, uncontrolled hemorrhage will ultimately be fatal. In general, an easy MEDEVAC is preferable to continued bedrest in the face of unrelenting bleeding. If the MEDEVAC is dangerous, rough or lengthy, bedrest and medication may be more advisable.

Inevitable abortion means that a miscarriage is destined to occur, but no tissue has yet been passed. This is sometimes called a "missed abortion."

This diagnosis is best made by ultrasonic visualization of the fetal heart and noting no movement. Alternatively, demonstrating no growth of the fetus over a one week period in early pregnancy confirms an inevitable abortion.

When ultrasound is not available, the diagnosis of inevitable abortion is made clinically. This clinical diagnosis is based on the presence of life-threatening maternal hemorrhage, or bleeding and cramping associated with a dilated cervix. In such clinical circumstances, the diagnosis of inevitable abortion can be made with confidence.

When bleeding is heavy, an inevitable abortion is treated as though it were an incomplete abortion. If bleeding is not heavy, then treatment may be postponed until the patient is transferred to a definitive care area. At the definitive care area, two alternative approaches are considered: D&C or awaiting a spontaneous abortion. Each approach has its own merits and limitations:

-

Awaiting a spontaneous abortion offers the benefit of avoiding surgery, but commits the patient to a day or more of heavy bleeding and cramping. A few of these women will experience an incomplete abortion and will need to have a D&C anyway.

-

Performing an automatic D&C has the benefit of quickly resolving the issue of a missed abortion, but commits the patient to a surgical procedure which carries some risks.

During the course of any abortion, spontaneous or induced, infection may set in.

Such infections are characterized by fever, chills, uterine tenderness and occasionally, peritonitis. The responsible bacteria are usually a mixed group of Strep, coliforms and anaerobic organisms. These patients display a spectrum of illness, ranging from mild, to very severe.

Usual treatment consists of bedrest, IV antibiotics, uterotonic agents, and complete evacuation of the uterus. If the patient does not respond to these measures and is deteriorating, surgical removal of the uterus, tubes and ovaries may be life-saving.

If your patient responds well and quickly to IV antibiotics and bedrest, you may safely continue your treatment. Remember, though, that she has the potential for becoming extremely ill very quickly and transfer to a definitive care facility should be considered.

Evacuation of the uterus can be initiated with oxytocin, 20 units (1 amp) in 1 Liter of any crystalloid IV fluid at 125 cc/hour or ergonovine 0.2 mg P.O. or IM three times daily. If the patient response is not favorable, D&C is the next step.

IV antibiotics should be started immediately. Reasonable antibiotic choices parallel those for PID, and include (Center for Disease Control, 1998):

1. Doxycycline 100 mg PO or IV every 12 hours, PLUS either:

-

Cefoxitin, 2.0 gm IV every 6 hours, OR

-

Cefotetan, 2.0 gm IV every 12 hours

This is continued for at least 48 hours after clinical improvement. The Doxycycline is continued orally for 10-14 days.

2. ALTERNATIVE ANTIBIOTIC REGIMEN:

-

Clindamycin 900 mg IV every 8 hours, PLUS

-

Gentamicin, 2.0 mg/kg IV or IM, followed by 1.5 mg/kg IV or IM, every 8 hours

This is continued for at least 48 hours after clinical improvement. After IV therapy is completed, Doxycycline 100 mg PO BID is given orally for 10-14 days.Clindamycin 450 mg PO daily may also be used for this purpose.

3. ANOTHER ALTERNATIVE ANTIBIOTIC REGIMEN:

-

Ofloxacin 400 mg IV every 12 hours, PLUS

-

Metronidazole 500 mg IV every 8 hours,

4. ANOTHER ALTERNATIVE ANTIBIOTIC REGIMEN:

-

Ampicillin/Sulbactam 3 g IV every 6 hours, PLUS

-

Doxycycline 100 mg IV or orally every 12 hours.

5. ANOTHER ALTERNATIVE ANTIBIOTIC REGIMEN:

-

Ciprofloxacin 200 mg IV every 12 hours, PLUS

-

Doxycycline 100 mg IV or orally every 12 hours, PLUS

-

Metronidazole 500 mg IV every 8 hours.

A woman with an unruptured ectopic pregnancy may have the typical

unilateral pain, vaginal bleeding, and adnexal mass described in textbooks. Alternatively,

she may have minimal symptoms. A sensitive pregnancy is almost invariably positive.

A woman with an unruptured ectopic pregnancy may have the typical

unilateral pain, vaginal bleeding, and adnexal mass described in textbooks. Alternatively,

she may have minimal symptoms. A sensitive pregnancy is almost invariably positive.

Patients with a positive pregnancy test and unilateral pelvic pain or tenderness may have an unruptured ectopic pregnancy and should have an ultrasound scan to confirm the placement of the pregnancy. If ultrasound is not available, then it is best to arrange for medical evacuation.

Alternative diagnoses which can cause similar symptoms include a corpus luteum ovarian cyst commonly seen in early pregnancy, or occasionally appendicitis. PID is characterized by bilateral rather than unilateral pain. With a threatened abortion, the pain is central or suprapubic and the uterus itself may be tender.

While awaiting MEDEVAC, the following are wise precautions:

-

Keep the patient on strict bedrest. She is less likely to rupture while lying absolutely still.

-

Keep a large-bore (#16) IV in place. If she should suddenly rupture and go into shock, you can respond more quickly.

-

Know her blood type and have a plan for possible transfusion.

-

A gentle, smooth MEDEVAC is preferable to a rough one, even if it takes longer.

-

The vibration during a helicopter ride or the jostling over rough roads in an ambulance or truck may provoke the actual rupture. Try to minimize this risk and be prepared with IV lines, IV fluids, oxygen, MAST (PASG) equipment, etc.

-

If she develops peritoneal symptoms (right shoulder pain, rigidity, or rebound tenderness), she may be starting to rupture and you should react appropriately.

Women with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy will have pain, sometimes unilateral and

sometimes diffuse. Right shoulder pain suggests substantial blood loss. Within a few hours

(usually), the abdomen becomes rigid, and the patient goes into shock. Sensitive pregnancy

tests are positive.

Women with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy will have pain, sometimes unilateral and

sometimes diffuse. Right shoulder pain suggests substantial blood loss. Within a few hours

(usually), the abdomen becomes rigid, and the patient goes into shock. Sensitive pregnancy

tests are positive.

Ultrasound can show fluid in the cul du sac but often fails to identify the ectopic pregnancy itself. Nonetheless, ultrasound, when available, can be a useful diagnostic aid in ruling out the presence of a normal, intrauterine pregnancy.

When ultrasound is unavailable, culdocentesis can demonstrate the presence of

significant amounts of non-clotting blood in the abdomen. While this doesn't confirm a

ruptured ectopic pregnancy, it is strongly suggestive of that. It provides a strong

indication for surgical intervention.

When ultrasound is unavailable, culdocentesis can demonstrate the presence of

significant amounts of non-clotting blood in the abdomen. While this doesn't confirm a

ruptured ectopic pregnancy, it is strongly suggestive of that. It provides a strong

indication for surgical intervention.

-

Palpate the uterus to determine its' shape and orientation.

-

Put a single-tooth tenaculum on the posterior lip of the cervix.

-

Pull the cervix toward you, straightening the uterus and stabilizing the posterior vaginal fornix.

-

After prepping with antiseptic, penetrate the posterior fornix in the midline with a spinal needle attached to a syringe. This will hurt. You will reach the peritoneal cavity in less than 1 cm.

-

Aspirate for fluid. Clear peritoneal fluid means no internal bleeding. Blood-tinged fluid usually means a traumatic tap. Bloody fluid means some bleeding, but not much. Gross blood suggests active bleeding. If there is doubt about the concentration of the blood in the specimen, perform a hematocrit on the aspirated fluid and compare it to the patient's hematocrit.

Treatment is immediate surgery to stop the bleeding. If surgery is not an available option, stabilization and medical evacuation should be promptly arranged. While awaiting MEDEVAC:

-

Give oxygen, IV fluids and blood according to ATLS guidelines.

-

Keep the patient at absolute rest.

-

Monitor urine output hourly with a Foley catheter.

-

Take frequent vital signs to detect shock.

-

Consider MAST trousers (PASG).

If abdominal surgery is not available, the outlook for a patient with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy is fair. Aggressive fluid and blood replacement, oxygen and complete bedrest will result in about a 50/50 chance of survival. If this approach is necessary, remember:

-

Try to maintain the urine output between 30 and 60 ml/hour.

-

If the pulse is >100 or urine output <30, she needs more fluid.

-

If she becomes short of breath and the lung sounds become "crackly," slow down the fluids as she probably is becoming fluid overloaded.

-

If she becomes short of breath and the lungs sounds dry, increase the fluids and give blood as she is probably anemic and in need of more oxygen carrying capacity.

-

As she loses blood into the abdomen, she will become distended. If she becomes so distended she can't breath, put a chest tube into the abdomen through a small, midline incision just below the umbilicus to drain off fluid or blood so she can breath.

-

A MAST or PASG Suit can be very helpful in tamponading the internal bleeding. Seriously consider it in this situation.

-

She may ultimately require as many as 15 or 20 units of blood.

Incomplete abortion and ruptured ectopic pregnancy are two of the most common medical emergencies requiring blood transfusion in women.

In a hospital setting, standard blood banking procedures apply, with the use of carefully cross-matched blood components as needed by the clinical situation.

In some operational settings, standard blood banking procedures may not be applicable or available. In these cases, direct donor to victim transfusion can be life-saving.

-

Use a donor with O negative blood ("Universal Donor"). Don't try to match, for example, a B+ victim to a B+ donor. While the accuracy of blood type records has improved, there is still a significant inaccuracy rate (as high as 5%) in the medical record laboratory reports, identification cards, and dog tags. If you try to match a B+ victim to a B+ donor (type-specific blood transfusion), you are twice taking a 5% risk of a mismatch. It is safer to take that risk only once. If the only available blood for a Rh negative victim is Rh positive blood, Rhogam may be used, in very large doses of 25-30, full-size, 300 microgram ampoules, IV, per unit of blood, to neutralize the Rh sensitizing effects of the Rh positive blood.

-

Arrange IV tubing so that there is a large-bore needle at each end. This is facilitated by use of a 3-way stopcock. If this is not available, you can simply cut off the tubing at the end and insert it into the hub of a needle. Sterile petroleum jelly can provide a seal and the needle is held tightly to the IV tubing with adhesive tape.

-

Position the donor about 3 feet higher than the victim. With the victim in a lower bunk, the donor would be in an upper bunk. With the victim on the floor or on the deck, the donor would be on a cot or packing crate.

-

Insert the IV into the donor and let the blood flow downhill through the tube until it reaches the other end. Clamp the tubing just long enough to insert the other end into the victims IV or vein.

-

Unclamp the tubing and allow time for about 1 unit (500 cc) of blood to flow into the victim. The exact amount of time would depend on the caliber of the tubing and needle, length of the tubing, height of the donor above the victim and doubtless other factors. In practice, allow about 10 minutes, but be prepared to stop it earlier if the donor becomes light-headed or dizzy.

-

Because fresh, whole blood has better oxygen-carrying capacity than banked units of packed RBCs, and it is prewarmed, and because it contains platelets, clotting factors and serum proteins, each unit has about twice the clinical impact of a unit of packed cells from the bank. If, based on your clinical experience, you believe a patient would benefit from two units of PRBCs from a blood bank, they will generally do well with a single unit of fresh, whole blood.

-

After the patient is transferred to a definitive care facility, it will be easier for them to identify the true, native blood type (major and minor blood groups) if they have a sample of blood taken from the patient prior to any transfusions. If time permits and the tactical situation allows for it, try to draw a single red-topped tube of the victim's blood prior to transfusion that you can send along with the MEDEVAC for use by blood banks further up the line.

Maternal Trauma During the First Trimester

During the first trimester, the uterus is protected within the pelvic bones. Trauma during this time will either be so severe as to cause a miscarriage (spontaneous abortion or fetal death), or else it will have no effect.

Miscarriage is a common event, normally occurring in one out of every 5 or 6 pregnancies. While trauma can cause 1st trimester pregnancy loss, it is exceedingly rare in comparison with other causes of miscarriage.

Catastrophic trauma includes such types of injury as maternal death, hemorrhagic shock, multiple compound fractures of the extremities, liver and spleen ruptures, to name a few. Catastrophic trauma during the first trimester is associated with subsequent miscarriage.

Non-catastrophic trauma includes bumps, bruises, fractures of small bones (fingers, toes), minor burns, etc. While such non-catastrophic injuries may be serious enough to require treatment, they are not associated with miscarriages.

Maternal Trauma During the Second and Third Trimester

Trauma occurring during the second and third trimester has different clinical consequences than during the first trimester. First trimester, minor trauma is not threatening to the pregnancy. During the second and third trimester, even relatively minor trauma can have significant adverse effects on the fetus. Such adverse effects include placental abruption, preterm labor, premature rupture of the membranes, uterine rupture, and direct fetal injury.

-

Rapid acceleration, deceleration, or a direct blow to the pregnant abdomen can cause shearing of the placenta away from its’ underlying attachment to the uterus. When this happens (placental abruption), the detached area will bleed and the detached area of the placenta will no longer function to supply oxygen to the fetus. A complete abruption is a disastrous event, life-threatening to both the fetus and the mother. Partial placental abruptions may range the full gamut from insignificant to the striking abnormalities seen in complete abruptions.

-

Premature labor may be provoked. In these cases, regular uterine contractions begin shortly after the trauma (within 4 hours) and progress steadily and result in delivery. Premature rupture of the fetal membranes can also occur, within the first 4 hours of injury and usually result in a premature delivery.

-

Direct fetal injury may occur, resulting in contusions, fractures or fetal death.

-

Uterine rupture can occur and usually result in the loss of the fetus.

The severity of the maternal injury may not correlate well with the frequency of adverse pregnancy outcome. Even minor trauma can have very serious consequences for the pregnancy.

The adverse effects, when they occur, are immediate (within the first few days of the trauma). There is probably no increased risk of preterm delivery, depressed Apgar scores, cesarean section or neonatal length of stay, after excluding the following immediate adverse effects:

-

Placental abruption within the first 72 hours of injury.

-

Rupture of membranes within 4 hours of injury.

-

Onset of labor within 4 hours of injury that resulted in delivery during the same hospitalization.

-

Fetal death within 7 days of the traumatic event.

Uterine contractions following trauma are common, although premature delivery caused by preterm labor is not. Actual preterm delivery resulting from premature labor (in the absence of abruption) probably occurs no more frequently among traumatized women than the general population.

Placental abruption is also known as a premature separation of the placenta. All

placentas normally detach from the uterus shortly after delivery of the baby. If any

portion of the placenta detaches prior to birth of the baby, this is called a placental

abruption.

Placental abruption is also known as a premature separation of the placenta. All

placentas normally detach from the uterus shortly after delivery of the baby. If any

portion of the placenta detaches prior to birth of the baby, this is called a placental

abruption.

A placental abruption may be partial or complete.

A complete abruption is a disastrous event. The fetus will die within 15-20 minutes. The mother will die soon afterward, from either blood loss or the coagulation disorder which often occurs. Women with complete placental abruptions are generally desperately ill with severe abdominal pain, shock, hemorrhage, a rigid and unrelaxing uterus.

Partial placental abruptions may range from insignificant to the striking abnormalities seen in complete abruptions.

Clinically, an abruption presents after 20 weeks gestation with abdominal cramping, uterine tenderness, contractions, and usually some vaginal bleeding. Mild abruptions may resolve with bedrest and observation, but the moderate to severe abruptions generally result in rapid labor and delivery of the baby. If fetal distress is present (and it sometime is), rapid cesarean section may be needed.

Because so many coagulation factors are consumed with the internal hemorrhage, coagulopathy is common. This means that even after delivery, the patient may continue to bleed because she can no longer effectively clot. In a hospital setting, this can be treated with infusions of platelets, fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate. In an operational setting where these products are unavailable, fresh whole blood transfusion will give good results.

Patients in an operational setting thought to have at least some degree of placental abruption should be transferred to a definitive care setting. While transporting her, have her lie on her left side, with IV fluid support.

Normally, the placenta is attached to the uterus in an

area remote from the cervix. Sometimes, the placenta is located in such a way that it

covers the cervix. This is called a placenta previa.

Normally, the placenta is attached to the uterus in an

area remote from the cervix. Sometimes, the placenta is located in such a way that it

covers the cervix. This is called a placenta previa.

There are degrees of placenta previa:

A complete placenta previa means the entire cervix is covered. This positioning makes it impossible for the fetus to pass through the birth canal without causing maternal hemorrhage. This situation can only be resolved through cesarean section.

A marginal placenta previa means that only the margin or edge of the placenta is covering the cervix. In this condition, it may be possible to achieve a vaginal delivery if the maternal bleeding is not too great and the fetal head exerts enough pressure on the placenta to push it out of the way and tamponade bleeding which may occur.

Clinically, these patients present after 20 weeks with painless vaginal bleeding, usually mild. An old rule of thumb is that the first bleed from a placenta previa is not very heavy. For this reason, the first bleed is sometimes called a "sentinel bleed."

Later episodes of bleeding can be very substantial and very dangerous. Because a pelvic exam may provoke further bleeding it is important to avoid a vaginal or rectal examination in pregnant women during the second half of their pregnancy unless you are certain there is no placenta previa.

The location of the placenta is best established by ultrasound. If ultrasound is not available, one reliable clinical method of ruling out placenta previa is to check for fetal head engagement just above the pubic symphysis. Using a thumb and forefinger and pressing into the maternal abdomen, the fetal head can be palpated. If it is deeply engaged in the pelvis, it is basically impossible for a placenta previa to be present because there is not enough room in the birth canal for both the fetal head and a placenta previa. An x-ray of the pelvis (pelvimetry) can likewise rule out a placenta previa, but only if the fetal head is deeply engaged. Otherwise, an x-ray will usually not show the location of the placenta.

Patients suspected of having a placenta previa in an operational setting need expeditious transport to a definitive care setting where ultrasound and full obstetrical services are available.

Toxemia of Pregnancy

Toxemia of pregnancy is a clinical syndrome characterized by elevated blood pressure, protein in the urine, fluid retention and increased reflexes. It occurs only during pregnancy and resolves completely after pregnancy. It is seen most often as women approach full term, but it can occur as early as the 22nd week of pregnancy. It's cause is unknown, but it occurs more often in:

-

Women carrying their first child

-

Multiple pregnancies

-

Pregnancies with excessive amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios)

-

Younger (<17) and older (>35) women

Ordinarily, blood pressure decreases during the middle trimester, compared to pre-pregnancy levels. After the middle trimester, blood pressure tends to rise back to the pre-pregnancy levels. Sometimes, blood pressure becomes elevated.

Sustained blood pressures exceeding 140/90 are considered abnormal and may indicate the presence of toxemia of pregnancy. For women with pre-existing hypertension, a sustained worsening of their hypertension over pre-pregnancy levels by 30 systolic and 15 diastolic is often used to indicate the possible presence of super-imposed toxemia.

The presence of hypertension and proteinuria are essential to the diagnosis of toxemia of pregnancy.

Pregnant women can normally lose up to 200 mg of protein in the urine in 24 hours. If protein loss exceeds 300 mg in 24 hours, this is considered proteinuria. Urine dipstick analysis for protein measures only a single point in time and does not necessarily reflect protein loss over 24 hours. Nonetheless, assuming average urine production of about a liter a day, and consistent loss throughout the 24 hour period*:

|

Category |

Negative |

Trace |

1+ |

2+ |

3+ |

4+ |

|

Dipstick Results |

<15 mg/dL |

15-29 mg/dL |

30 mg/dL |

100 mg/dl |

300 mg/dl |

>2000 mg/dL |

|

Equivalent |

<150 mg |

150-299 mg |

300-999 mg |

1000-2999 mg |

3-20 g |

>20 g |

Some but not all women with toxemia demonstrate fluid retention (as evidenced by edema or sudden weight gain exceeding 2 pounds per week). Some but not all women with toxemia will demonstrate increased reflexes (clonus).

Toxemia of pregnancy is subdivided into two categories: pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. The difference is the presence of seizures in women with eclampsia.

The clinical course of pre-eclampsia is variable. Some women demonstrate a mild, stable course of the disease, with modest elevations of blood pressure and no other symptoms (mild pre-eclampsia). Others display a more aggressive disease, with deterioration of both maternal and fetal condition (severe pre-eclampsia). Some of the points of differentiation are listed here. Notice that there is no "moderate" pre-eclampsia, only mild and severe.

|

Problem |

Mild Pre-Eclampsia |

Severe Pre-Eclampsia |

|

Blood Pressure |

>140/90 |

>160/110 |

|

Proteinuria |

1+ (300 mg/24 hours) |

2+ (1000 mg/24 hours) |

|

Edema |

+/- |

+/- |

|

Increased reflexes |

+/- |

+ |

|

Upper abdominal pain |

- |

+ |

|

Headache |

- |

+ |

|

Visual Disturbance |

- |

+ |

|

Decreased Urine Output |

- |

+ |

|

Elevation of Liver Enzymes |

- |

+ |

|

Decreased Platelets |

- |

+ |

|

Increased Bilirubin |

- |

+ |

|

Elevated Creatinine |

- |

+ |

The definitive treatment of pre-eclampsia is delivery. The urgency of delivery depends on the gestational age and the severity of the disease. Severe pre-eclampsia usually requires urgent delivery (within hours) more or less regardless of gestational age. In this situation, the risk of serious complications (placental abruption, growth restriction, liver failure, renal failure, hemorrhage, coagulopathy, seizures, death) will generally take precedence over the fetal benefit of prolonging the pregnancy. Induction of labor is preferred, unless the maternal condition is so tenuous and the cervix so unfavorable that cesarean section is warranted.

In milder cases, particularly if remote from term or with an unfavorable cervix, treatment may range from hospitalization with close observation to initial stabilization followed by induction of labor following preparation of the cervix over the course of several days. In the most mild, selected cases, outpatient management might be considered with careful monitoring of maternal and fetal condition.

Traditionally, magnesium sulfate has been used to treat pre-eclampsia. Magnesium sulfate, in high enough doses, is a reasonably effective anti-convulsant, mild anti-hypertensive and mild diuretic. While other agents may be more potent in each of these individual areas, none combines all three of these features into a single drug. The world's experience with magnesium sulfate to treat pre-eclampsia is extensive and these unique features provide considerable reassurance in employing it in these clinical settings. Magnesium sulfate is given IM, IV or both. All are effective reasonably effective in preventing seizures. Because the risk of eclampsia continues after delivery, MgSO4 is frequently continued for 24 to 48 hours after delivery.

-

Magnesium sulfate 10 gm in a 50% solution, one-half (5 gm) IM, injected deeply into each upper outer buttock quadrant. Every 4 hours thereafter, Magnesium sulfate 5 gm IM is injected into alternating buttocks. Repeat injections are postponed if patellar reflexes are absent. Because these injections are painful, 1 ml of 2% Xylocaine is sometimes added to the magnesium. This schedule gives therapeutic levels of magnesium (4-7 meq/L)

-

Because IM magnesium sulfate does not initially achieve its therapeutic levels for 30 to 45 minutes, in cases of severe pre-eclampsia, an IV bolus of magnesium sulfate can be added. 4 gm magnesium sulfate as a 20% solution can be given slowly over at least 5 minutes, followed by the IM injections described above.

-

Magnesium sulfate 4 gm IV, slowly, over at least 5 minutes, followed by 2 gm IV/hour.

The therapeutic margin (distance between effective dose and toxicity) is relatively thin with magnesium sulfate, so some precautions need to be taken to prevent overdose. The biggest problem with MgSO4 is respiratory depression (10 meq/L) and respiratory arrest (>12 meq/L). Cardiovascular collapse occurs at levels exceeding 25 meq/L. MgSO4 levels can be measured in a hospital setting, but clinical management works about as well and is non-invasive.

The patellar reflexes (knee-jerk) disappear as magnesium levels rise above 10 meq/L. Periodic checking of the patellar reflexes and withholding MgSO4 if reflexes are absent will usually keep your patient away from respiratory arrest. This is particularly important if renal function is impaired (as it often is in severe pre-eclampsia) since magnesium is cleared entirely by the kidneys.

In the case of respiratory arrest or severe respiratory depression, the effects of MgSO4 can be reversed by the administration of calcium.

Calcium Gluconate (Ca++) 1 gm IV push.

If BP is persistently greater than 160/110, administer an antihypertensive agent to lower the BP to levels closer to 140/90. One commonly-used agent for this purpose is:

Hydralazine 5-10 mg IV every 15-20 minutes. Don't drop the pressure too far (below a diastolic of 90) as uterine perfusion may be compromised.

Eclampsia means that maternal seizures have occurred in association with toxemia of pregnancy.

These tonic/clonic episodes last for several minutes and may result in bite lacerations of the tongue. During the convulsion, maternal respirations stop and the patient turns blue because of the desaturated hemoglobin in her bloodstream. As the attack ends, she gradually resumes breathing and her color returns. Typically, she will remain comatose for varying lengths of time. If convulsions are frequent, she will remain comatose throughout. If infrequent, she may become arousable between attacks. If untreated, convulsions may become more frequent, followed by maternal death. In more favorable circumstances, recovery occurs.

Eclampsia should be aggressively treated with magnesium sulfate (described above), followed by prompt delivery, often requiring a cesarean section. If convulsions persist despite MgSO4, consider:

-

Valium 10 mg IV push

The HELLP Syndrome is characterized by:

-

Hemolysis

-

Elevated Liver Enzymes

-

Low Platelets

This serious condition is associated with severe pre-eclampsia and the treatment is similar...delivery with prophylaxis against maternal seizures.

Unlike pre-eclampsia, patients with HELLP syndrome may continue to experience clinical problems for days to weeks or even months.

If the HELLP syndrome is mild, it may gradually resolve spontaneously, but more severe forms often require intensive, prolonged care to achieve a favorable outcome.

Home · Introduction · Medical Support of Women in Field Environments · The Prisoner of War Experience · Routine Care · Pap Smears · Human Papilloma Virus · Contraception · Birth Control Pills · Vulvar Disease · Vaginal Discharge · Abnormal Bleeding · Menstrual Problems · Abdominal Pain · Urination Problems · Menopause · Breast Problems · Sexual Assault · Normal Pregnancy · Abnormal Pregnancy · Normal Labor and Delivery · Problems During Labor and Delivery · Care of the Newborn

|

Bureau of Medicine

and Surgery |

Operational

Obstetrics & Gynecology - 2nd Edition |

This web version of Operational Obstetrics & Gynecology is provided by The Brookside Associates Medical Education Division. It contains original contents from the official US Navy NAVMEDPUB 6300-2C, but has been reformatted for web access and includes advertising and links that were not present in the original version. This web version has not been approved by the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. The presence of any advertising on these pages does not constitute an endorsement of that product or service by either the Department of Defense or the Brookside Associates. The Brookside Associates is a private organization, not affiliated with the United States Department of Defense. All material in this version is unclassified.

This formatting © 2006

Medical Education Division,

Brookside Associates, Ltd.

All rights reserved